Patron: Nadine Plachta

Recently my attention was drawn to the post-earthquake situation in Lapchi, an area located on the northernmost fringes of Dolakha District. In the course of my PhD project I have become increasingly interested in the country’s remote border regions with Tibet and how borderland communities perceive, narrate, and confront an increasing level of state control exercised by the Nepalese and Chinese governments.

Following the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the new power on the highest region on earth entered into a series of boundary agreements and treaties with Nepal in 1960. These included a strategic exchange of two villages previously in Nepal for two villages previously in Tibet (see Shneiderman 2013). In geopolitical negotiations between the two Himalayan neighbors the former Tibetan region of Lapchi was allocated to Nepal for reasons of state security and economic interests. The Lapchi people were officially recognized as „border citizens“ within the Sino-Tibetan Nepal border zone, a designation that allows them to travel for trade as far as Tashi Khang, the first settlement on the Tibetan plateau, without a passport or visa.

I first visited Lapchi in April 2012 and since then I have been maintaining close contact with members of the local community who have migrated to Kathmandu. Among them is Karma Woeser, secretary of the Lapchi Association and a contact person for this organization. Sitting in a local tea stall in the Tibetan enclave of Boudhanath in the Kathmandu Valley three months after the earthquake had struck, he said to me: „The Lapchi Association is appealing for donations to help cover the expenses for hiring helicopters, buying food and medicines, and for post-earthquake rescue.“ When I inquired further, he added: „The funds will also be used for long-term rebuilding or restoration of the people’s houses, community buildings, and pilgrimage sites.“

It is not surprising that government relief efforts have not reached the mountainous community yet. Due to the low population of about seventy persons and their insufficient proficiency in the Nepali language, along with the inaccessible terrain they inhabit at the country’s periphery, the people of Lapchi are easily disregarded when it comes to distributing state benefits. However, by collecting donations from community members who have migrated to the country’s capital city or abroad, the Lapchi Association managed to dispatch two helicopters for immediate relief. Injured villagers could thus be brought for proper medical treatment to Kathmandu shortly after the earthquake had devastated most of the houses.

The people of Lapchi inhabit two settlements in the region, Lumnang (3620 m) and Lapchi (4250 m), which serve respectively as winter and summer habitats for 13 families. Lapchi village is situated at the foot of Lapchi Khang, a mountain range which is a pilgrimage destination well known throughout the Tibetan cultural area. The biography of Jetsun Milarepa (1052-1135), who is considered one of Tibet’s most famous saints and poets, states that he meditated for many years at Lapchi. Villagers offer praise to the caves of Rechen Phug, Dudul Phug, and Ze Phug, which are situated on the main mountain, and maintain that the cotton-clad hermit left such marks of his presence as footprints and sacred springs in the region. The main monastery of Lapchi, Chöra Gephel Ling, was built by the Tibetan philosopher Shabkar Tsogdrug Rangdrol (1781-1851). In its vicinity, seven widowed women aged 65 years and older are spending their remaining years in simple houses of stone and wood. One sign of Lapchi’s widespread reputation are the secluded refuges dotting the mountain, where currently 16 persons from across the Himalayan region (Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, India) are undergoing strict meditation practices.

An hour to the west of Lapchi village is a rather unprepossessing mountain pass which leads to the Tibetan village of Tashi Khang in Nyalam County of Shigatse Prefecture. At a short walking distance inside Tibet, the Chinese Army in 2014 installed a fence and surveillance cameras from one side of the narrow valley to the other in order to control movement at the border zone. The Lapchi villagers, who take yak caravans to purchase commodities at Tashi Khang, cross this border frequently. They are highly dependent on market access, because the harsh Himalayan climate only allows the cultivation of barley on the limited agricultural land, while potatoes and spinach are restricted to kitchen gardens. People further consume dairy products, both fresh and processed, produced by large bovine herds. There is no electricity, broadcast station, or access to mobile phone networks in Lapchi. The monastery keeps a satellite phone for emergency usage only. The nearest motorable road which connects the region with the Nepalese lowlands ends at Lamabagar, a small Sherpa village at a two days‘ walking distance. Wooden ladders and bridges along steep cliffs rule out the use of mules for the transport of goods on this rough terrain.

During the devastating earthquakes that hit Nepal on April 25 and May 12, 2015, numerous houses in Lapchi and Lumnang villages were destroyed. The Lapchi monastery and the pilgrimage sites also suffered severe structural damage. Immediately ensuing landslides buried a group of lowlanders walking on the path from Lamabagar to Lumnang, which since then has remained inaccessible via that route. Currently, helicopters are the only means of reaching Lapchi, and even they are held in check in by the highly unstable weather in the region.

In view of these circumstances, the SAI Help Nepal initiative acceded to Karma Woeser’s request to send relief materials to Lapchi, where food is still the top priority, along with the evacuation of the sick, injured, and elderly to Kathmandu.

Update October 24, 2015

October 13 was a mild autumn day in the Kathmandu Valley. The soft mist and morning sunlight immersed the city in a gentle red. The taxi was already waiting outside the South Asia Institute’s Kathmandu Office. It had not been easy to find a vehicle the day before and I was expected to pay the double price to Kathmandu’s domestic airport. The blockade caused by the agitating Madhesis in the southern plains had been inhibiting the entry of fuel tankers and other essential commodities to the valley for the past three weeks. To make matters worse, the neighboring state of India supported the Madhesis‘ claims for more inclusion under Nepal’s new constitution, leaving boarding schools without cooking gas and hospitals without medicine.

The cargo to be dispatched to Lapchi had already reached the airport. Karma Woeser, who had flown with the October 9 delivery to the Himalayan border region, had carefully prepared the load before his departure. The funds from the SAI Help Nepal initiative allowed us to book three helicopters, supplying the people of Lapchi with such relief material as rice, dal, dried soya chunks, oil, and sugar. We acquired these helicopters by using the services of Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF), a Christian organization that had successfully been conducting flights to assist earthquake affected areas since the first tremor had occurred. Its operation in Nepal is funded by UK Aid and gives government-registered organizations the opportunity to book helicopters for fifty percent of the common price with Fishtail Air. The third helicopter to Lapchi would part Kathmandu on October 19.

The helicopter flight took forty-five minutes. Captain Deepak Rana, with over 5,000 hours of flight experience, skillfully avoided low-hanging clouds and maneuvered the helicopter through the narrow Lapchi valley. At the end of the valley, at the confluence of two rivers, we caught sight of Lapchi Khang. At the bottom of the snow-covered mountain, situated between Lapchi village and Chöra Gephel Ling Monastery, members of the local community were waiting on the helicopter pad. Landing on the rough terrain, the helicopter stirred up so much dust that the people turned their backs to us. When the rotor came to a standstill, we were greeted cheerfully, and the cargo was unloaded and distributed equally (taking account of the size of households) to villagers, the elderly, monks, and persons on retreat. Then Karma Woeser flew back to Kathmandu in order to make preparations for the helicopter that would pick me up six days later.

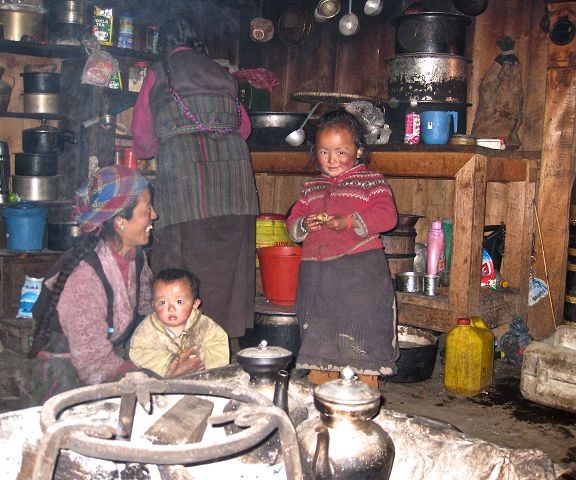

When the excitement subsided, people gradually slipped away back to their daily work, and I was given a room in the monastery. The head monk lent me colorful Chinese blankets and a sleeping mat, and reminded me to close the main wooden door whenever I left the compound to prevent the yaks coming in. They apparently had developed skills to open the door with their massive horns, their sights set on grazing the lush grass growing inside the monastery. I took the meals with the mother of Karma Woeser, a woman in her seventies. She lived in a small stone house nearby, together with her daughter and two children of a distant relative. The four of them shared two beds next to a cooking stove. I had brought enough food for all of us, knowing that eatables were scarce. I did not want to be a burden to anyone. I was surprised, however, when I learned that I had to prepare the vegetables myself. „We don’t know how to cook them,“ Karma Woeser’s mother said amusedly with twinkling eyes in her weather-beaten face. „We live mostly on tsampa and potatoes.“ Afterwards I took the empty pans as a sign that they liked the new dishes.

The next days I explored the area, did a damage assessment of the affected buildings and collected approximately 20 hours of interview material on experiences of the earthquake. Sonam Dekyi, a woman that I visited on one of my strolls, recalls that the villagers were at the winter abode when the earthquake happened. She said that most of the people were collecting grass at the time the earthquake struck. Dispersed along a mountain slope, they each called out to other members of the small community. In shock, some stayed under rocks for two days with nothing to eat. She herself frequently heard landslides coming down the mountains as the aftershocks continued. Paralyzed by these events, Sonam Dekyi packed her belongings on the yaks and headed for Lapchi village, the summer abode, rather than go about repairing her house. Three of the elderly women living next to the monastery shared a tent a tourist had previously left in the area. Tsering Dolma was one of them. She said they lived on instant noodles for three days, as they were afraid to go into their stone houses, many of which had collapsed walls and were only held together by the timber framework. She and her friends knew, however, that living outside posed different challenges, for near the retreat sites one monk was attacked by a bear, which, like many other wild animals living in the mountains, had itself taken fright from the tremors. Now Tsering Dolma expressed fear of the upcoming winter. She still remembers vividly how last year the snow had obstructed all walking paths: „In this region, the snow sometimes falls so high that I even cannot catch sight of the monks of the monastery which is located only a few meters away.“

These conversations revealed that many questions and emotions still linger beneath the surface. Most of my interlocutors maintained that food for winter, construction material for repairing the houses, and equipment for tending to the walking paths are the most important necessities for them. Once the trails are open, they will no longer be cut off from the Tibetan plateau or the Nepalese lowlands, where essential commodities can be purchased.

On the last day, the morning dew evaporated with the first rays of the sun. While waiting for the helicopter to arrive, I watched the villagers loading their belongings on the sturdy backs of yaks. They were preparing to leave for lower altitudes at Lumnang. Soon only persons on retreat, monks, and the elderly women would be left to confront the cold winter at the foot of Lapchi Khang.